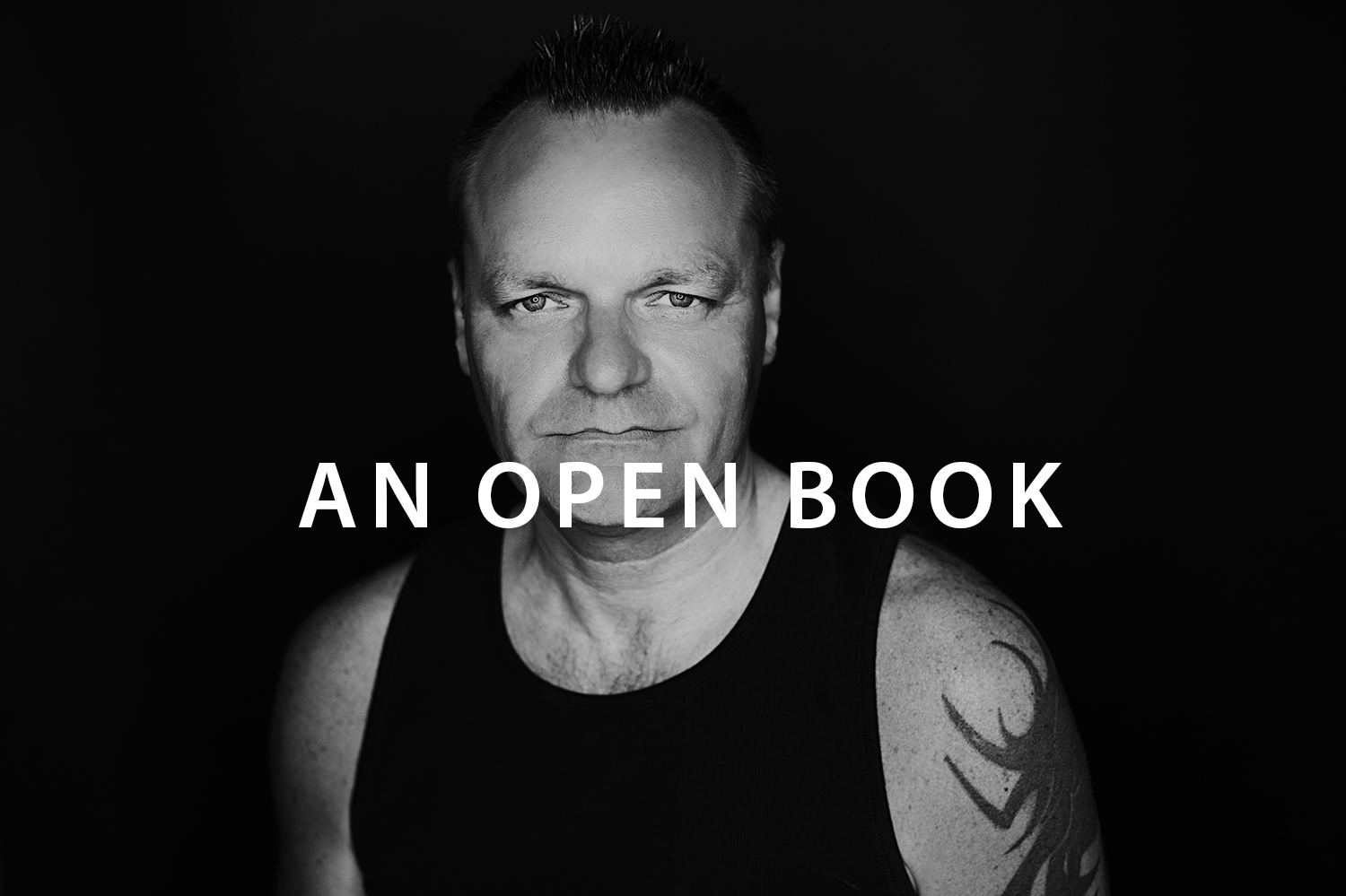

adam

“In recovery, I got everything back — and then some.

I won’t ever be shutting up about that.”

For the entirety of my addiction – many sad, painful years of car accidents, overdoses, barroom brawls and street fights, failed relationships, small-time legal skirmishes and stints at rehabs – everyone wanted me to admit I had a problem, to talk about it.

Then, after I got clean and sober and became a husband, father, hockey dad and a union president that negotiated my co-workers salaries and medical benefits, many people wanted me to put it behind me, to shut up about it.

The planet witnessed the train wreck, yet I was supposed to cover it up after I got that bad boy back on the rails, which was no small feat.

That never made any sense to me.

So I sing like a bird, telling basically everybody that I’m a recovering addict.

Why do I disclose it?

First, I can’t help myself. It’s often hard to have an honest conversation with someone without bringing it up. Like it or not, the truth is that my life has been dominated by addiction. I have been in its grip or in a state of constant maintenance and eternal vigilance to stay out of it. Yet, once in a state of arrest and remission, addiction doesn’t define me. Freed from the need to use, I’m neither fragile nor fractured.

Second, while obviously not proud of everything I did in my addiction, I’m not ashamed of being an addict. It’s an allergy of sorts. I can’t stop once I start. So now I don’t start. Sounds easy, but getting clean is hard, and I’m infinitely more proud of getting out of the hole I dug than I am ashamed that I dug it in the first place.

Third, I think it’s important for people to realize that all addicts aren’t 24/7 scumbags, even in their active addictions. I didn’t spend my days microwaving kittens or freebasing nuns. Quite the contrary: One night, in the late 1980s, I pulled over to change a tire for a nun who had a flat, despite the fact that I had drugs in my car and should have gone straight home. (I broke my anonymity to her, of course, telling her all about the chemical-free comeback I was going to make one day soon, very soon, probably next week. She thanked me for the road call and said she’d pray for me.)

Fourth, saying I’m in recovery really means only one thing: I don’t drink or do drugs – ever. So all I’m actually divulging is that I’m in the same category as Gladys, the teetotaler from the sewing circle, or Bob, the guy who ties his own flies for trout season and never touches the stuff. That doesn’t exactly put me in a camp where I’m a threat to anybody.

I’m a newspaper reporter and just got done working on a three-day series on heroin’s resurgence. (The series getting assigned to me was a serious case of typecasting.) During the reporting, I had the privilege of interviewing many young addicts who are very public about their recovery.

They were on the record for the interviews. They let us take their photographs and put video of them on our website. They didn’t do it because they were on ego trips. They did it because they wanted to help addicts seeking recovery.

Our stories were stronger for it. We didn’t’ have to only use their first names and take shadowy pictures of them so they couldn’t be identified. Because the stories were strong, readers connected. About 700 people packed a high school auditorium for our community forum seeking information and help. (When the young addicts were introduced, by the way, they weren’t shunned. They were greeted with raucous applause.)

I’m proud of these young addicts’ public stances. It takes courage. I have a DUI older than some of them, but I look up to them.

If they can do it, so can I.

I also listened to families who lost children to overdoses. One of the young men was 24 when he died in 2012. The parents formed a group that has gotten a good samaritan law passed so anyone who calls 911 during an overdose can’t get prosecuted for a drug charge. They also helped with the passage of a law that increased community access to Narcan, the drug that can reverse opiate overdoses.

More than once in 1986, when I was 24, I was four to six heartbeats away from the same fate as the young man who died. Dumb luck or God’s grace gave me a different outcome. His dad thinks it’s important that addicts speak out, if they feel comfortable doing so, to help de-stigmatize addiction.

I agree with him.

I’m 52 and first got clean and sober when I was 26. I relapsed with alcohol and prescription painkillers in December 2006. It took me 4.5 years to get back into treatment on April 3, 2011. I’ve been clean and sober ever since.

The relapse was inexcusable. Chalking it up to me having a disease is a total copout. I knew how to stay clean and I didn’t. I was deeply ashamed, because, unlike my first round in active addiction, I was a dad this time. I could barely make eye contact with people or finish a sentence in rehab. I felt like a failure, and appropriately so.

“Left untreated, addiction takes everything.”

Left untreated, addiction takes everything. You don’t even see some of the losses slipping away until they’re already gone.

It’s insane. We should talk about that.

On the flip side, addicts clean up quite nicely.

I’m not only physically there for my children today, I’m emotionally present as well.

My son is 19 and my best friend. We’re way smarter than the general managers for the Eagles, Sixers, Flyers and Phillies – and prove it during our laughter-filled conversations every day.

My daughter, 16, is my closest confidante. After the heroin series ran, she told me she was not only proud of me for writing it, but for all the work I’ve done since getting out of rehab in 2011.

In recovery, I got everything back — and then some.

I won’t ever be shutting up about that.

My name’s Adam Taylor. Definitely not anonymous.